This post has been republished via RSS; it originally appeared at: New blog articles in Microsoft Community Hub.

Neha Shah and Jonathan Larson

Resilient organizations weather crises by adapting with flexibility, ultimately emerging stronger. That is easier said than done, of course. While many organizations may strive toward resilience, leaders have limited clarity into how to measure progress, much less manage it. The difficulty lies in resilience being an interdependent, systemic function of responses from individual employees, workgroups and the organization.

To address this complex problem, we turn to organizational network analysis (ONA), which allows us to visualize and measure the complete system, while also breaking it down to meaningful chunks. Organizational network analysis concentrates on the pattern of connections formed when employees collaborate through meetings, emails, instant messages or calls (i.e., the organization’s collaborative network). These connections provide the means through which employees and workgroups exchange information and create knowledge, both to be productive and to maintain support. Organizational network analysis provides critical insights into resilience by enabling measurement of adaptivity; we can quantify and visualize when, whether and how people change their connections in response to crises, the extent to which they maintain or add new connections, and whether these connections remain with their own workgroup or whether they span working groups.

With the belief, then, that organizational resilience can and should be intentionally created, we offer guidance rooted in organizational networks. To be sure, achieving resiliency requires a long-term view, and continued measurement. We focus here on employees’ very first adaptations to crisis in the wake of the Covid-driven shift to remote work. If leaders can understand employees’ differing adaptive strategies, they can take informed actions to encourage resilience. In a future article, we explore how ONA provides insights into the shifting organizational structure, and how leaders can course correct to sustain resilience.

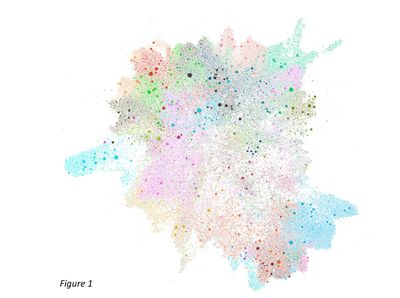

Partnering with a specialized team in Microsoft Research that merges artificial intelligence with business intelligence, we created an organizational network from the 1.87 million connections shared by over 92,000 de-identified Microsoft employees. An AI algorithm sorted employees into working groups based solely on digital collaboration, agnostic of role, function, level, or other organizational attributes. Simply put, employees grouped together tend to collaborate more together. Here is a view into that network, with each dot reflecting an anonymous employee and each color reflecting a working group. The network shape results from collaboration patterns; for example, the group in teal on the left likely engages in limited collaboration with most others in the organization, while groups near to one another likely collaborate more together.

To determine which employee connections to include in our analysis, we utilized thresholds including a baseline level of activity across emails, calls, meetings, and instant messages sent by one employee to another in any given month. For example, to include a connection from Sally to Fred, Sally must have sent 10 emails to Fred or 40 instant messages, or some equivalent combination of all four over the course of the month. Furthermore, we only include focused communications with 4 or fewer recipients. These thresholds ensure we include connections that reflect more ‘meaningful’ connections. Our analyses focus on ‘outbound connections,’ which consist of sent emails and Teams instant messages, along with participation in meetings and calls. All employee results are aggreged to working group levels to maintain privacy. Here is what we learned:

Start simply—focus on continuity: Determine how much shock the organization experienced

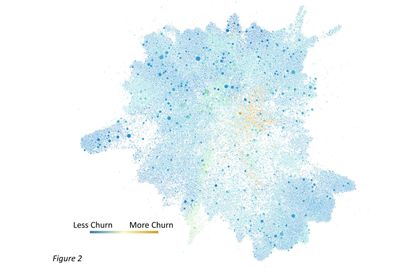

We first wanted to understand how much shock the organization had experienced. Shocks can encourage instability, and so we measured the amount of churn in employee networks. We considered whether employees kept up with their existing connections by measuring retained connections per working group between February and March, compared to retention between January and February. The wide swath of blue in Figure 2 shows most employees did not drop their existing connections. Despite an unprecedented shift in the way we work, most employees retained more connections than in a ‘normal’ working environment—keeping 3% more of their prior connections than the previous month. This limited churn indicates a strong sense of stability in the organization at large.

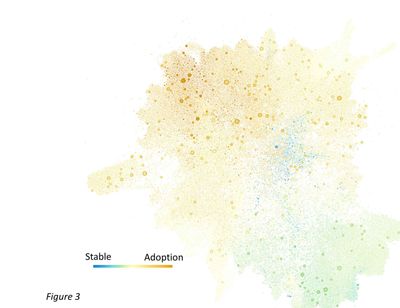

We attribute this stability in part to technology adoption. Between February of this year and March, when most work from home orders went into place, we found employees differed in the way they stayed connected to colleagues. Teams located primarily in the Seattle area faced a hurdle that others, like the already remote sales organization, did not. These collocated employees were connecting via email and meetings; but they had to quickly transition from their face-to-face connections to Teams calls and chats. They had to adopt new technologies to stay connected (shown in orange and yellow in Figure 3), while those who were already working remotely could remain stable in their technology use (shown in green). This hurdle may have been eased in some cases where teams were distributed across multiple offices and so had comfort in working regularly with others across offices and time zones.

Here is a key for resilience—these employees did not withdraw from these informal connections built on hallway conversations or stop-by-the-desk chats, which research has shown are crucial for feelings of engagement and trust. Instead, these working groups shifted how they connected—and so, they stayed connected.

Overcoming crisis situations would be impossible if the organization were to become either exceedingly instable or exceedingly rigid in response to shocks. Resilient organizations must be able to withstand shocks, even while being flexible to navigate through them. Here, and above, we find the organization maintained stability at levels consistent with ‘normal’ non-crisis times—our first indicator of resilience in the face of crisis.

Identify how the organization adapted to the shock

Changes in collaboration:

In addition to keeping their existing ties, most members of the organization increased the size of their networks through the crisis by an average 13% between February and March, to 23 outgoing connections. They did so by adding connections at a rate 24% more than in the previous month. This is not inevitable behavior by any means. That members of most groups formed new connections at all runs opposite to expectations of threat rigidity. When people face threats they often ‘freeze,’ focusing on doing what they have always done and connecting with those they find familiar-thereby becoming more rigid in their behavior.

We did find some tendency toward familiarity here also, as these employees formed 70% of their new connections to people within their own working groups. These familiar connections may create a sense of shared understanding. Research shows that when groups become more densely connected, the increased interconnectivity means that people hear similar information from many others in the group. This type of echo facilitates a shared understanding and identity among group members. From a productivity standpoint, the shared understanding can help the group move efficiently toward time-sensitive goals in crisis situations.

Perhaps we could attribute some of this increase to our newfound ability to account for connections, since collocated employees may have communicated face-to-face rather than through the digital means we measure. If this were the primary explanation, then we would expect a limited change in the count of connections across working groups (where employees likely already connect through digital means). Surprisingly, we saw the formation of new connections that span outside of the working group increase by 22% over the prior month. Counter to the notion of freezing, this shift suggests that employees extend beyond their comfort zones to form new connections or perhaps reactivate old connections to help the organization guard against threats associated with this crisis. For example, employees may start cross-group virtual teams to address common problems of remote work.

This cross-group connectivity enables the broad information sharing that has been deemed essential for organizational resilience. Even while company leaders share information often, there remains great uncertainty in unknown situations. To gain a sense of control, people may reach out to access “new” information that can offer a feeling of control or empowerment. In addition, employees may synthesize this novel information to find new ways of looking at problems or contexts that they had not previously considered to pivot current offerings to meet customer needs. Some of these connections may facilitate coordination between groups. And finally, because of these many connections that cross working groups, employees learn how others view the organization’s structure, processes, and functions, and begin to assemble a shared vision of the organization.

Recognize that groups vary in shock responses—with good reason

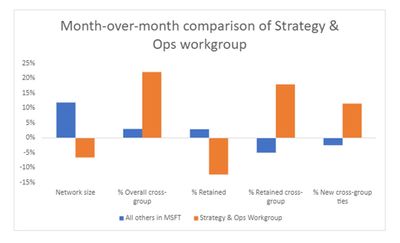

While we have concentrated thus far on the groups in which members kept their existing connections, notice the exception in the orange island in the middle of Figure 2. These working groups displayed a connectivity profile that seemed nearly opposite from the rest of the organization. Deeper analysis revealed that these were the only working groups in which people collaborated with fewer others during this crisis than before it. Their networks shrunk by 7% in March (the rest of the organization grew by 13%, as we noted above).

They changed their networks principally by keeping fewer of their existing (pre-crisis) connections (keeping only 52% of connections, versus the rest of the organization keeping 62%), especially to others in their own working group. They added fewer new connections than others but were more likely to add connections that crossed working groups, at a rate 18% higher than the prior month. These changes led to a pared down network that became overall 22% more external leaning than in the prior month (the rest of the organization became 3% more externally leaning).

What happened here? This workgroup includes members of Microsoft’s strategy and operations organization, manning the organization’s control center through the crisis. Members of this critical group very nimbly adapted their networks to current needs. They did so by paring down connections within their own working group and keeping and forming connections across groups, likely to those only most acutely relevant to regain stability for the organization and its employees.

As we mentioned earlier, for resilient organizations, navigating through crises requires flexibility. We see this flexibility demonstrated by the organization at large, and most by the group charged with steering the organization through the current crisis. Were this group to remain rigidly focused on the same ways of working prior to the shift or to be slow in their reaction to it, the organization could be weakened and less able to continue to weather future shocks. Its adaptivity offers a positive indicator of resilience.

Toward resiliency: measuring adaptivity through employee collaborations

Like all organizations, Microsoft faces a long, unchartered path forward. We moved first toward continuity to regain stability and now toward rebuilding, all the while fortifying for long term resilience. Our post here describes just the initial shift from the ‘old normal’ to working from home. While it is an early look into how the organization changed, we learned that most employees kept existing collaborations even while adding new connections that spanned working group boundaries. We learned that organizational groups changed their behaviors to stay connected. And finally, we saw our ‘control center’ quickly pivot its networks to address current needs. We found all these changes took place within the first month of the crisis.

These differences suggest that groups respond differently to crises and should receive differential support from organizations over time. Control tower groups (strategy and operations, primarily) face critical impacts of business disruption on operations. They must manage extraordinarily novel problems requiring cross-disciplinary input, including the transition to remote work, while the sensitivity of their work requires putting aside all non-essential communication. As a result, these groups must pivot their collaborative projects and connections to adapt their network to pressing priorities. For managers in this group, burnout should be front of mind as these employees likely work at high paces with limited connectivity. The network changes of this group may play a key role in continuity, recovery and long-term resilience.

Most working groups must focus on their normal work (reflected in kept collaborative connections) and still address the novel problems or opportunities that benefit from getting more diverse input (reflected in boundary spanning connections). Without acute pressure from a single front, individuals may find it difficult to prioritize. Managers should conduct regular 1:1 meetings, and supply increased clarity on priorities when needed. In addition, managers may also need to help employees prevent collaborative overload, particularly for informal ‘experts’, who might be highly sought out for information from their colleagues.

Collocated teams may need more support versus already remote/distributed teams. As an organization, future research should address whether and how we can make the most of our training and adoption budget by focusing on groups facing the biggest transition and making sure they have access to best practices as they adapt to the new normal.

Overall, even the best prepared organizations will face crises. To be resilient, employees and their groups must have the right connections to adapt and emerge stronger from it.

Thanks to Jessalynn Uchacz, Nikolay Trandev, and Darren Edge, who contributed to this research and report. This paper is a joint project between Microsoft Research and Workplace Intelligence.